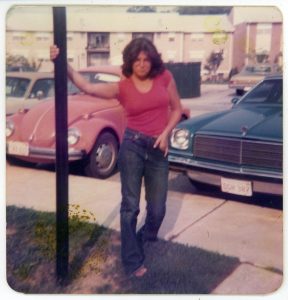

My breasts are too big. Professionals from the age of 11, they skipped their training and went right to the C cup.

When I flash on growing up with my breasts, I remember mostly humiliating things: my piss-yellow gym uniform gaping at the snaps; the obvious size discrepancy between the two as revealed by the green Speedo I wore for swim practice and meets every day of the summer for all my high-school years; being called Moose Miller, after the comic strip, by two boys in the sixth grade who had not learned to like breasts yet—or they had and simply acted as boys in the sixth grade do (which, come to think of it, is not unlike the way many men do). Perhaps my most vivid recollection is standing naked in front of a male plastic surgeon as he took pictures of them during a consultation for a breast reduction that I never had.

When I flash on growing up with my breasts, I remember mostly humiliating things: my piss-yellow gym uniform gaping at the snaps; the obvious size discrepancy between the two as revealed by the green Speedo I wore for swim practice and meets every day of the summer for all my high-school years; being called Moose Miller, after the comic strip, by two boys in the sixth grade who had not learned to like breasts yet—or they had and simply acted as boys in the sixth grade do (which, come to think of it, is not unlike the way many men do). Perhaps my most vivid recollection is standing naked in front of a male plastic surgeon as he took pictures of them during a consultation for a breast reduction that I never had.From my teen years on, I often slept in a bra when I had my period, and my breasts spent the majority of my pregnant nights in a much larger one. They are the first body part to gain weight, and they are the last to lose it.

My sister, my husband, and many of my girlfriends regularly point out their size to me, as if they are separate entities controlled by remote, which I use to inflate or deflate them at will. Some people, mostly men, talk to them instead of my nice eyes.

Last year’s mammogram hurt so much that, despite my having lymphoma and needing to do regular cancer screenings, I postponed this year’s mammogram by more than four months. And this one, performed two weeks ago, hurt so much that they still throb from the crushing.

What bothers me most about my breasts—more than ill-fitting tops and now-wrinkled cleavage and soreness and wires poking into my ribcage for thirteen hours a day (even now, as I sit in my bed and compose this sad ode to them)—are the divots in my shoulders, the permanent cuts in my bones.

What bothers me most about my breasts—more than ill-fitting tops and now-wrinkled cleavage and soreness and wires poking into my ribcage for thirteen hours a day (even now, as I sit in my bed and compose this sad ode to them)—are the divots in my shoulders, the permanent cuts in my bones. Nothing, save a fluffy pillow, could have stopped the elastic straps from cutting grooves into my shoulders. Surely not fatter straps, which would have likely caused fatter grooves. I couldn’t have chosen no bra or a strapless bra or even a racer back, which would have simply moved the groove closer to my neck. During the eighties, however, I reduced the discomfort and the cutting effect by placing my shoulder pads undermy bra straps. Alas, shoulder pad style was short lived and never made a comeback—unlike bell bottoms, hip huggers, and tube tops. (That I couldn’t wear a tube top is probably the most positive result of my breast size.)

In the summer, my divots are most visible. Though the swimsuit straps should fit nicely into the grooves, where they will stay put and are not subject to sliding down, my breasts are too heavy to stay put. A length of yarn ties the straps together at the back to hold me up.

Most of the time, no one sees my physical deformity except for my husband, my daughter, and a random friend for whom, when I want sympathy, I will occasionally yank over my shirt and slip down my bra strap. But I can see it. More important: I can feel it.

Friends joke sometimes when they hear I’m thinking again about a breast reduction. “You can give me what you don’t want,” one woman says; another replies, “Maybe we can split it!”

I feel a little like a traitor now, having spent the last 600 words dissing the girls, both of whom have served me well in a few of life’s most important arenas. Despite the abnormalities and the pain and the disfigurement they’ve caused me over the years, I don’t hate them nearly as much as I hate my ankles.

I write about my breasts and my struggles with the consequences of their size because I get a little weary of the insensitive messages sent by deceptive advertisers and well-meaning friends alike. Every day, someone posts a so-called positive, uplifting message about how wonderful our bodies are and how we should love them and not fall prey to Madison Avenue’s unachievable lingerie-model standard.

Our feelings about our bodies go far deeper than what we look like in the mirror. I don’t know which is more insulting—the notion that beauty is a size 0 or the impression that I am so shallow that I would reject my body parts because of their appearance alone—or that appearance doesn’t also hinder function.

So I’ll say it: I don’t love my body. I sometimes don’t like it. But every day, I stuff parts into fabric contraptions and make the best of what works and what doesn’t. And my relationship with those parts is an intimate, personal one (though it’s not, now, a private one) influenced by gym teachers and doctors and parents and lovers and children and friends and bullies and disease and books and music and, yes, advertising, because we don’t live in a vacuum.

Like America itself, the motto of the body should not be “love it or leave it.” It should be “love it or try to make it better.” And that’s probably what most of us do.